13 Feb Rediscovering Solzhenitsyn

Kevin Moss is Director of Operations at Christian Heritage and a PhD candidate in intellectual history.

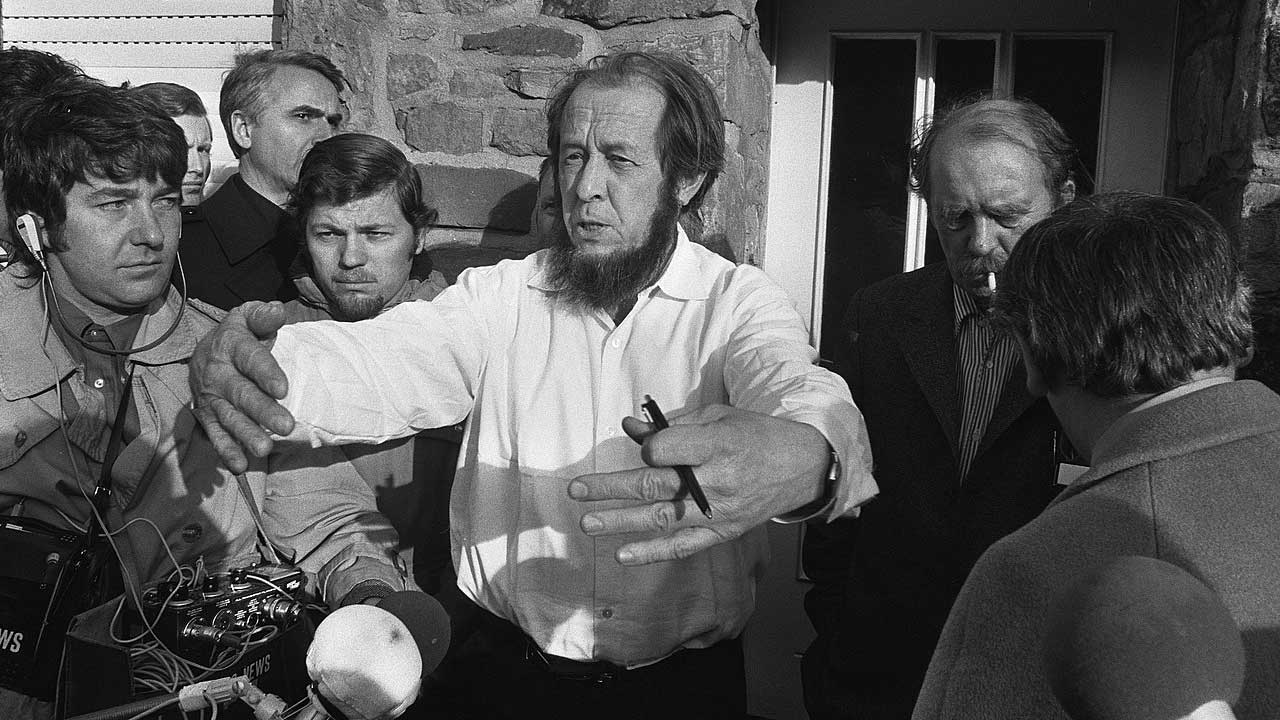

I’m afraid I was a bit of a late developer when it came to reading Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s magnum opus, The Gulag Archipelago. In the end, won over I suspect by Jordan Peterson’s emphasis of its significance, in 2017 I bought the condensed volume which incorporated all three instalments of Solzhenitsyn’s monumental treatment of the phenomenon of the Soviet Gulags. My review on the page linked above will hopefully convey my sense of the utter relevance of what is described here.

There are several layers to a work such as this. One is as a record of a particular period in history, describing a cultural phenomenon which happened on the other side of the world, and which, in its sheer scale and brutality is almost beyond Western comprehension. The Wikipedia listing of the Gulag camps is a helpful first point of reference, as it powerfully conveys the scale of the whole machinery of oppression, reminding us that this is very far from being the kind of minor consideration that is of little relevance. Solzhenitsyn makes it clear that there is a very specific kind of human pathology which leads directly to this treatment of our fellows – so neither geographical nor cultural remoteness should excuse complacency. After all, as the recent James Norton film demonstrates, there was no shortage of Westerners, including leading politicians, prepared to applaud the Communist regime for its proclaimed successes, despite that remoteness. In a more contemporary context, that lingering admiration and support for Stalin persists through organisations such as the Stalin Society, and various incarnations of the Communist Party in the UK. And as we have noted in the media, whilst various factions are intent on tearing down statues in the West, a new statue of Lenin was erected in Germany in 2020, and an older one has been elevated to a new position in New York. You can find out about the worldwide distribution of Stalin statues here, and of Lenin statues here. Needless to say, there is a noticeable absence of iconoclastic agitation in relation to these visual reminders of one of the greatest evils the world has ever seen.

Solzhenitsyn does not merely narrate his own experience, in the way that some kinds of contemporary account do, as a simple retelling of a series of events where he is the principal witness. He does not cave in to the postmodern turn of leaving his reader to draw their own conclusions from a bare narrative. In fact, the nature of his thought processes is laid out throughout his account: there is a painful and continual reflecting on what is happening to him and his compatriots, what he is learning about himself, and what he is discovering about his own culture. David Robertson provides a rather helpful summary of some of these key themes in his own treatment. It is this characteristic of the writing which is most stimulating to our own consideration – Solzhenitsyn is not merely some lab rat, or some tiny component of a bigger dehumanised mass which is consigned to the Siberian wastes. He self-identifies as a unique person who is capable of standing outside of himself in order to observe his own suffering and draw conclusions from it, even whilst he simultaneously remains a prisoner of the subjective experience of it. I still find it remarkable that he was able to write the chapters of the entire book within his own head, and commit the text to memory in readiness for his release.

It is significant, of course, that the nature of Solzhenitsyn’s experience brought him from a Marxist worldview to a very firm Christian commitment. He experienced firsthand the fruits of an ideology which plays with human populations by assigning us to groups, categories that ideologues come up with. He fully understood the proposition that once we have arrived at a model of society which is carved up into groups, then the next and inevitable stage is that those groups are pitted against each other. There are ‘in’ groups and ‘out’ groups. There is an inequitable apportionment of resources or ‘rights’ depending upon which kind of group one is assigned to. There is the ascendancy of a particular category of group, depending upon nothing more objective than the current prevailing ideology. Solzhenitsyn saw right through all of that. It is notable that The Gulag Archipelago includes so many intriguing character studies of individuals, as if the author is contrasting his increasingly Christianised view with the results of Marxist groupthink. Having worked for the last 38 years of my life within a now heavily regulated sector, it seems that Solzhenitsyn’s analysis forms a highly relevant antidote to the current lottery of regulation, where success or suffering are the direct product of group membership, rather than of individual circumstances.

A recent sermon by Rico Tice on Jesus’ parable on the ‘Lost Sheep’ (Luke 15:1-7) made that point quite powerfully. The Pharisees (the religious legalists) reacted negatively to Jesus’ popularity with people who were damaged, or frail, or outcasts by sneering “This man welcomes sinners, and eats with them.” In their binary worldview, the Venn diagram comprised two groups, ‘sinners’ and ‘religious’, and there was zero overlap. Jesus responds to that kind of simplistic reductionism by telling three interrelated parables which demonstrate that (a) everyone’s in the same boat, and (b) God sees the value of each individual human being. This was exactly the discovery that Solzhenitsyn made for himself within the Gulag. I finish with his own words:

“If only it were all so simple! If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being. And who is willing to destroy a piece of his own heart?”

(From The Gulag Archipelago, by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn)

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.