15 Dec Ideology and the Dismissal of History

Kevin Moss is a Christian Heritage trustee and PhD candidate in intellectual history.

One of the many joys of historical research is that one gets to meet great minds that have somehow fallen through the cracks of popular history. One such, for me, has been Johann Georg Hamann (1730-88), a profound German Enlightenment thinker with a propensity for dark and enigmatic writings. In recent years, there has been a gentle flourishing of translations of his literary contributions (many remain untranslated from the German), and I have recently benefited enormously from John R. Betz’ After Enlightenment, the Post-Secular Vision of J. G. Hamann (2012, Wiley-Blackwell).

Hamann’s is an unusual mind, given his context. He turned from the sterility of continental Enlightenment to a robust, evangelical Christian faith – and in that turning became something of a focus for secular acquaintances who regarded his sincere faith as an affront to their values. Through their influence, he was introduced to Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) in the hope that the great philosopher would reclaim this errant Enlightenment heretic, but what actually emerged was an improbable friendship, one where Hamann certainly gave as good as he got. Essentially, Hamann provided one of the best, and certainly one of the earliest, rebuttals to Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, and there is every reason to think that everything that Kant learned about the Scottish Enlightenment philosopher, David Hume (1711-1776), came to him through Hamann’s mediation.

Hamann enjoyed a fruitful intellectual collaboration with Johann Gottfried von Herder (1744-1803), and it turns out that his writings were a profound influence on Søren Kierkegaard (1813-55), the Danish philosopher. It is a mysterious thing to discover an individual who has simultaneously been so overlooked, and at the same time, so pivotal in the development of the more prominent European thinkers. Hamann is, in microcosm, proof positive that those sweeping Enlightenment tropes are simply not an accurate reflection of reality. Here is a man, intensely and consistently rational, and in every sense embodying the Lockean underpinnings of this worldview, who recognises the fundamental, presuppositional importance of faith, as the means of making sense of the world. It is, in many ways, something of a shock to see how immediately, and how clearly Hamann decoded Diderot’s Encyclopédie as a largely reductionist attempt to rewrite history on the basis of the new materialistic polemic. Peter Gay, and others like him, wants us to see this period as a face-off between the ‘new paganism’ of Enlightenment thinking, and the ‘old superstitions’ of a Christian worldview, but that kind of simplistic, binary distinction is disproved in a moment when one considers the contributions of thinkers such as Hamann, or Jonathan Edwards (New England), or Isaac Watts (Britain), or John Witherspoon (Scotland and New Jersey). Not only does one not have to make the choice, but Hamann takes exceptional glee in demonstrating that the new Enlightenment thinkers such as Kant are relentlessly plagiarising the Christian canon, in order to argue their point. One is reminded of the present-day ‘Atheist Churches’ meeting in deconsecrated church buildings, and in a very real sense aping the very thing that they disparage (during times when it was permissible to meet).

One of Hamann’s great contributions is the exploration of the significance of philology, and he describes himself in his writings as “a lover of the Word”. Ultimately, that applies to his view of Scripture, but in a more mediate sense, you can see it work out in the very serious way in which Hamann treated the text on the page. For example, he sees science as “a matter of hermeneutics, of interpretation” (Betz), and argues that all philosophy is necessarily grounded in a textual tradition. Whereas the continental philosophes relentlessly continued their strategy of grinding language down into an essentially meaningless combinations of noises, the byproduct of an undirected, telos-free process, Hamann saw language as something far more profound, the means by which we reliably handle reality, and may have a degree of confidence that we are doing so. Betz tells us that he had a particularly clear view of the way in which regulation, through the forcible imposition of its own ideological overlays, and aesthetic norms, has the effect of “depriving language of its primal power”. In Hamann’s day, such an idea was radical and novel but with the benefit of hindsight, we can see that it is prophetic: the fruit of that kind of unrestrained secularism has seen the proliferation of regulation beyond the human capacity to comprehend it, coupled with the radicals’ hegemony over our language. Last night, I was discussing with academic colleagues the wisdom of using acronyms such as ‘BAME’, coined (fairly recently) by proponents of Critical Race Theory (CRT). The new, politically-correct acronym promulgated this week, is swiftly succeeded by the next iteration, and woe to the luddite who has the misfortune to use last week’s version. In this secular-sanctioned chaos, where accepted words and concepts are sucked into the maelstrom, violently centrifuged, and spat out of some ideological orifice, language itself has become weaponised against the unwary user. It has been adroitly converted into a tool of oppression, and it is being used with brutal force within our higher education system, the media, and other key loci of influence by those occupying an arguably extreme position on the political spectrum. The Free Speech Union, inaugurated early this year, is working flat out to defend individuals (many academics) who were either simply doing their job, or articulating blindingly obvious points of historical or scientific fact. Generally, it has been found that the CRT activists have been acting outside of the parameters of the law, as they seek to attack dissenting voices, demonstrating that this is as much of a power game as has been the redefinition of language.

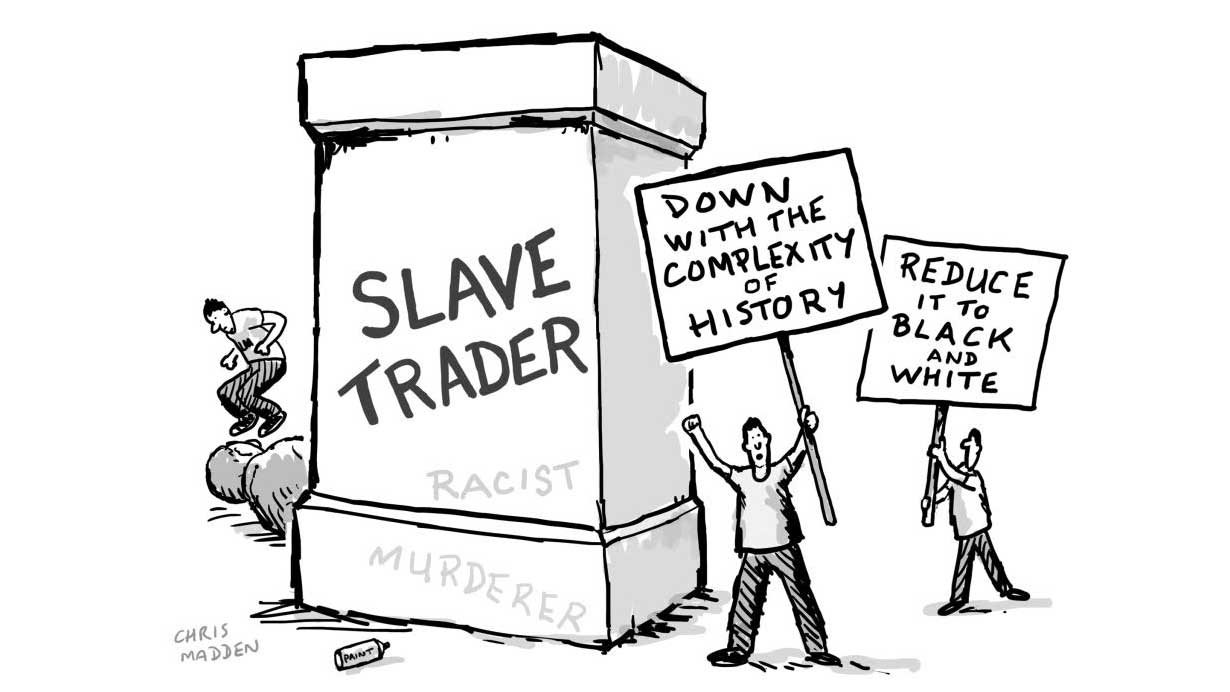

The modern, value-free, evolutionary view of history carries with it an implicitly patronising and dismissive view of the past, especially when elements of that past are inconvenient for the new, polarised view of reality. The Medieval period, a time of huge cultural and scientific advance is invariably dismissed as the ‘dark ages’, and prophetic individuals such as Johann Georg Hamann are systematically ignored because they do not fit the ideologically-simplified version of history, where the dogmatic presupposition appears to be that Christian belief cannot possibly be enlightening.

And a cowed, submissive and often highly-paganised ‘church’ is letting them get away with it. A smattering of Luthers, Calvins or Knoxs would be helpful, right now.

N.B. This post first appeared at www.theobloggie.wordpress.com

Photo credit: Chris Madden and Don’t Divide Us

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.